Broadway (1915 to 1962)

During the years that Berlin developed as a songwriter, New York’s theater district developed as well. The creation of a Times Square subway stop in 1904 turned the area surrounding Broadway and 42nd Street into a mecca for theater developers, producers, songwriters, and performers. Titans of the entertainment field such as Florenz Ziegfeld, George M. Cohan, Al Jolson, Victor Herbert, and Jerome Kern would turn “Broadway” into both an industry and a mythology. Berlin - who would have significant relationships with each of those individuals - seized the opportunity to make his name in the explosive and exploding world of Broadway.

Although several of Berlin’s songs had previously been placed in various revues and vaudeville presentations on Broadway, his first full score was for Watch Your Step, which opened at the New Amsterdam Theater in 1914; starring the dancing superstars of their era, Vernon and Irene Castle, the show featured Berlin’s signature “counterpoint” duet: “Simple Melody/Musical Demon.” The next year, Berlin followed up with Stop! Look! Listen!, which introduced “I Love a Piano” and, in 1916, he co-wrote the score for the revue The Century Girl with Victor Herbert.

Berlin’s roll on Broadway ground to a screeching halt when the United States entered the Great War in December of 1917. Two months later, Berlin became an American citizen and by May was inducted into the U.S. Army as a private. Fervently patriotic, but tested by the rigors of army life, Berlin sought a compromise with his superiors: might he put together a revue about army life - much the way that some navy sailors had done for their branch of the service?

The resulting revue, Yip, Yip, Yaphank, under Berlin’s supervision, deployed hundreds of soldiers, rehearsed among the potato fields of Yaphank, Long Island, and ultimately moved to Broadway - “Presented by Uncle Sam,” as the program credit ran -where it played 32 performances.

Berlin entered the boisterous post-war period with a vengeance. He wrote the full score of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1919 (considered the producer’s finest edition) with songs including “A Pretty Girl is Like a Melody,” which became permanently associated with Ziegfeld. After contributing to a handful of songs to the 1920 edition of the Ziegfeld Follies, Berlin struck out on his own as a producer. With veteran Broadway entrepreneur Sam H. Harris, he built the Music Box Theatre on West 45th Street as a venue for his own work. Beginning in 1921, Berlin produced four annual revues at the Music Box, introducing such songs as “Say It With Music,” “All Alone,” and “What’ll I Do?”. Unlike Ziegfeld’s extravagant revues (or the more lubricious Earl Carroll’s Vanities), the Music Box Revues emphasized subtle performances and tasteful productions.

When the revues ran their course, Berlin turned to a nearly impossible assignment: crafting a score for a book musical that attempted to contain the rambunctious and zany Marx Brothers. Collaborating with the most prominent comic dramatist of his day, book writer George S. Kaufman, Berlin composed The Cocoanuts, a hit that also played in London and became one of the first musicals from Broadway to be filmed in sound in 1929. (Berlin’s enduring ballad “Always” was written before The Cocoanuts, but Kaufman - who referred to himself as a “curable romanticist” - felt that a more realistic lyric would be “I’ll be loving you Thursday” and the song was instead released as a one-off and subsequently became a standard.) After contributing the full score to the Ziegfeld Follies of 1927, Berlin briefly turned his prodigious energies away from Broadway and concentrated on motion pictures.

As impressive as his output was in the 1920s, Berlin’s personal life was also in an upswing. In 1924, he met socialite Ellin Mackay, the daughter of Clarence Mackay, an Irish-Catholic billionaire who had inherited the vast fortune made by his father as a silver miner in Nevada. Ellin, some fifteen years younger than Berlin, would earn a reputation as an impressive essayist and chronicler of the Jazz Age. Berlin and Ellin’s romance - with its “star-cross’d” implications - became the fodder for tabloid journalists in the middle of the Roaring Twenties. The elder Mackay fulminated against the religious and age differences between his daughter and Berlin; when the couple married quietly at New York’s City Hall on January 4, 1926, Mackay disinherited his daughter. Berlin’s own considerable personal income supported the couple - he assigned the royalties of “Always” to Ellin, for example - and they enjoyed one of the most successful marriages among show business couples, lasting 62 years, until Ellin’s death in 1988.

Their children included Mary Ellin Berlin (born 1926); Linda Louise Berlin (born 1932); and Elizabeth Irving Berlin (born 1936). A son, Irving Berlin, Jr., died in infancy in 1928. Ironically, Berlin’s wealthy father-in-law Mackay was nearly completely wiped out by the Stock Market Crash toward the end of 1929, while Berlin, whose investments were largely in his own musical copyrights, not only survived the Depression, but prospered artistically and financially.

While the Depression did little to lift Broadway’s fortunes, it did inspire a new kind of socially engaged musical and encouraged writers to introduce elements of political satire and commentary. Berlin’s first Broadway musical of the 1930s was Face the Music (1932). With a book by the up-and-coming comic dramatist Moss Hart (and directed by Hart’s new writing partner George S. Kaufman), the musical was a revue within a narrative, about a Broadway show purposely constructed to be a flop - this, decades before The Producers. Berlin and Hart teamed up the following season to concoct what is generally considered to be the finest (and one of the last) revues between the wars, As Thousands Cheer. One of the few non-narrative musical shows of the time to be constructed around a guiding principle - in this case, the context of a daily newspaper with its various articles and features - As Thousands Cheer gave audiences a whirlwind tour of a variety of Depression-era preoccupations from around the globe. As Thousands Cheer was innovative both in content and form: Berlin tackled the pertinent issue of lynchings in the South (“Supper Time”), and at a time when audiences were used to a series of reprises of the hit tune for the finale, he confounded expectation by putting in a brand-new number (“Not For All the Rice in China”). Introducing such standards as “Easter Parade” and “Heat Wave,” the show ran 400 performances and provided stage career highlights for performers Clifton Webb and Ethel Waters.

After a hiatus spent mainly writing scores for Hollywood (*see Hollywood section), Berlin returned to New York to write another hit, Louisiana Purchase, in 1940, a satire about political malfeasance in New Orleans that starred the comedy duo of William Gaxton and Victor Moore. Inventively, Berlin opened the show with a satirical frame in which a famous lawyer of the time, Samuel J. Liebowitz, sang about the possible libelous ramifications of the story to follow. It ran 444 performances, introduced the song “It’s a Lovely Day Tomorrow,” and was filmed in 1941 with Bob Hope.

The declaration of war against the Axis forces in December of that same year deferred Berlin’s plans to bring a big revue back to Broadway; asked by the War Department to create another morale boosting show on the order of Yip, Yip, Yaphank, Berlin threw his energy instead into creating This Is The Army. Once again, the revue’s vast ensemble was recruited from the U.S. Army, but this time the show included a number of black soldier/performers, making it an unprecedented landmark for the integration of members of the armed forces. While keeping the general frame of the previous revue, This Is The Army updated its topics, incorporating such World War II elements as the Stage Door Canteen and the Army Air Force.

Once again, Berlin supervised the production and performed his own reprise of “Oh, How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning.” After opening on Broadway in July 4 of 1942, the show toured the country; was filmed (in a slightly more narrative version) in Hollywood in 1943; and toured army bases near battle lines in Europe and the South Pacific, off and on, through the fall of 1945. For Berlin’s extraordinary efforts - which included raising more than six million dollars for the Army Emergency Relief Fund - he was awarded the Medal of Merit.

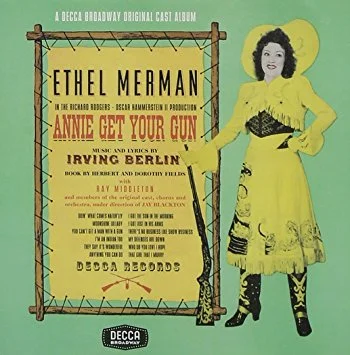

The post-war atmosphere on Broadway was charged with the 1943 success of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!, which brought the narrative musical to a new level of sophistication as well as critical and popular acceptance. Toward the end of the war, lyricist Dorothy Fields had the brainstorm of creating a musical about sharpshooter Annie Oakley to star Ethel Merman. She asked Rodgers and Hammerstein to produce the new show and Jerome Kern to compose the score. When Kern suddenly passed away in 1945 before the writing process could begin, the team invited Berlin to step in as songwriter (Fields generously stepped aside and wrote the book with her brother Herbert). Although initially reticent to commit to such a narrative-driven project, Berlin spent a weekend trying his hand at a few songs; they fit the material perfectly and were avidly accepted by his collaborators, which eventually included director Joshua Logan. Annie Get Your Gun opened in May of 1946 and ran for 1,147 performances - the longest run of any Berlin stage musical.

Two months after the show opened on Broadway, five renditions of songs from its score filled the top eleven ranks of the Billboard charts, a feat unequalled by any other Broadway composer. A signature show from the “Golden Age” of the American musical, Annie Get Your Gun had a successful national tour, a successful London production (which ran longer than the Broadway version), was made into a major MGM film in 1950, and has subsequently played in every conceivable venue, including two major New York revivals.

Berlin’s next stage musical, Miss Liberty (1949), was about the publicity surrounding the dedication of the Statue of Liberty; for the finale, Berlin even set a keystone of American history - Emma Lazarus’ sonnet engraved on the Statue of Liberty, “The New Colossus” - to his own music. The show involved some extraordinary collaborators, such as Robert E. Sherwood, Moss Hart, and Jerome Robbins, but other than the introduction of “Let’s Take an Old-Fashioned Walk,” it was a commercial and personal disappointment for Berlin. The following season, a contemporary satire on American diplomacy, Call Me Madam, was far more successful, running 644 performances. Whimsically inspired by the career of Washington hostess Pearl Mesta, the musical, which starred Ethel Merman, introduced “The Best Thing for You” and a counterpoint melody, “You’re Just in Love.” Like Annie Get Your Gun, the show had a successful national tour and a film version (1953), this time with Ethel Merman reprising her stage triumph.

Berlin attempted a number of musical projects in the late 1950s that never got off the ground, but he made a highly anticipated return to Broadway with Mr. President in 1962, a light-hearted look at the young and attractive residents of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Although the musical set a record for the largest advance sale of its time, Mr. President didn’t run past the season, nor did it deliver any hit songs. When Annie Get Your Gun was revived in 1966 by the Music Theater of Lincoln Center, Berlin wrote a brand-new counterpoint number for star Ethel Merman, “An Old-Fashioned Wedding,” which has earned a permanent place in the show’s score. It was to be Berlin’s last original song performed on Broadway and, fittingly, it was one of his most delectable.

No other composer-lyricist could match Berlin’s longevity on Broadway, nor his ability to produce memorable material in such varied forms as the revue, the musical comedy, and the narrative musical.

Written by Laurence Maslon - an arts professor at NYU’s Graduate Acting Program. He has written numerous books and documentaries about musical theater and edited Berlin’s As Thousands Cheer for the Library of America anthology American Musicals (1927-1969).